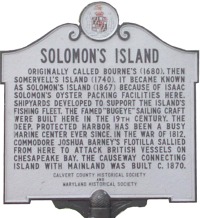

Solomons is located at the southern tip of Calvert County, in Southern Maryland, where the Patuxent River meets the Chesapeake Bay. The island itself was variously known as Bourne’s Island (about 1680), Somervell’s Island (1740- 1814) and Sandy Island (1827- 1865). The land was most likely part of the early land grant of Eltonhead Manor. Early land records show that the island was owned by a number of individuals until 1865 when a tract of eighty acres called “Sandy Island” was sold to Isaac Solomon. This area has played little part in the significant events that shaped the tidewater area in the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Tobacco farming brought the first settlements and towns and associated commerce to the Patuxent region. Except for the burning of Point Patience in 1780, the American Revolution was chiefly fought to the south of Solomons. The War of 1812 came much closer as farms and settlements along the Patuxent River became targets for the British forces as the British fleet made its way up the Patuxent River on its way to burn Washington.

Solomons is located at the southern tip of Calvert County, in Southern Maryland, where the Patuxent River meets the Chesapeake Bay. The island itself was variously known as Bourne’s Island (about 1680), Somervell’s Island (1740- 1814) and Sandy Island (1827- 1865). The land was most likely part of the early land grant of Eltonhead Manor. Early land records show that the island was owned by a number of individuals until 1865 when a tract of eighty acres called “Sandy Island” was sold to Isaac Solomon. This area has played little part in the significant events that shaped the tidewater area in the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Tobacco farming brought the first settlements and towns and associated commerce to the Patuxent region. Except for the burning of Point Patience in 1780, the American Revolution was chiefly fought to the south of Solomons. The War of 1812 came much closer as farms and settlements along the Patuxent River became targets for the British forces as the British fleet made its way up the Patuxent River on its way to burn Washington.

Eight months after President James Madison declared war on Great Britain, initiating the War of 1812, British Navy frigates and men-of-war blockaded the Chesapeake Bay and began raiding along the rivers of the Tidewater.

Eight months after President James Madison declared war on Great Britain, initiating the War of 1812, British Navy frigates and men-of-war blockaded the Chesapeake Bay and began raiding along the rivers of the Tidewater.

Captain Joshua Barney, having served with distinction during the Revolutionary War, came out of retirement with a dramatic proposition for William Jones, Secretary of the Navy. Barney recommended the construction of a number of lightly armed, shallow draft barges or galleys that could be both sailed or rowed. These would be faster and more maneuverable than the larger and more heavily laden British vessels. He received approval to begin construction in August, 1813 and on May 24, 1814, promoted to Commodore, Barney led the Chesapeake Flotilla against a British force vastly superior in both numbers and weapons.

Check out the Summer 2000 Bugeye Times to find out more about the gunboats of St. Leonard’s Town during the War of 1812

During the Civil War when Marylanders often fought against Marylanders, there was virtually no impact on this practically uninhabited point of land.

Following the Civil War and the economic boom that flourished, Solomons began to come into prominence. The nearby harbor off Drum Point had provided a sheltered anchorage for sailing vessels bound up and down the Chesapeake. With the surge in the oyster industry after the Civil War, Maryland became the world’s leading supplier of this product. It was inevitable that someone would discover the potential of Solomons as a center for oyster processing and the construction and repair of oystering vessels.

Isaac Solomon, a Baltimore businessman, established a cannery together with associated services and workers’ housing and was advertising his canning establishment as “Solomons Island.” He leased small lots on the island to many people who paid a yearly rent varying from $9 to $21. In 1870, the community received official recognition when the United States Postal Service opened an office.

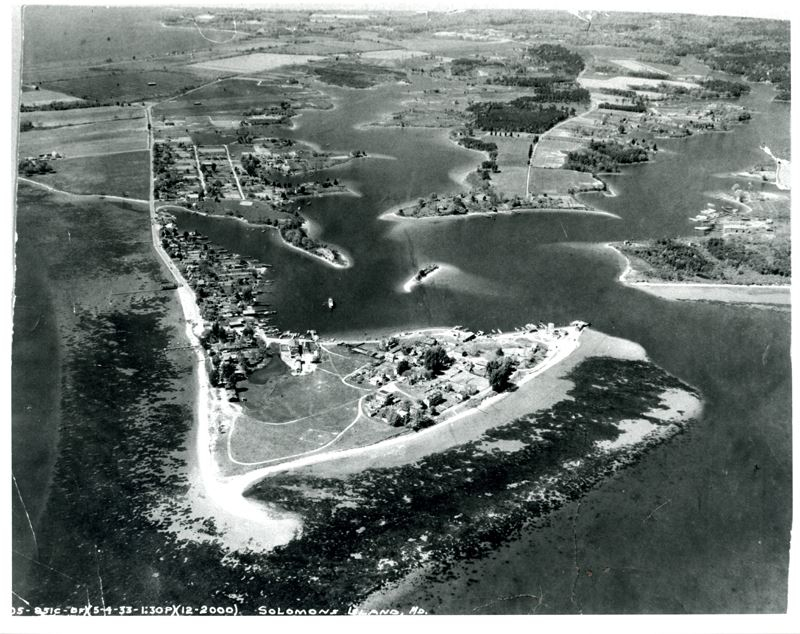

Benefiting from the accessible position at the mouth of the Patuxent River, the town quickly built a reputation as a center for shipbuilding and repairing, seafood harvesting, and the provisioning of sailing vessels engaged in the oystering business. The census of 1880 listed fifty-one different households and 237 residents. The Solomons fishing fleet exceeded five hundred vessels, many of which were locally built. Captain Thomas Moore owned nearly one hundred vessels, the largest private fleet in the state. Solomons was soon becoming the most important commercial center in Calvert County.

More bugeyes (large, deck-over sailing canoes, typically constructed of shaped logs) were built in Solomons than in any other community on the bay. The first framed bugeye, Clyde, was built by Isaac Davis on Solomons Island in 1877.

In the November 12, 1892 issue of the Calvert Gazette, Solomons was described as: “There are about one hundred houses upon the island, including some stores which do an active business in the oyster season, and three shipyards. It is chiefly occupied by oystermen and fishermen. “

By the 1890s, Solomons consisted of two distinct communities – Solomons Island proper and Avondale on the mainland. The two were separated by a shallow stretch of water spanned by a rickety bridge. With a population, at this time, of about 400, most of the business activities were centered on the island and Avondale was mainly residential. Other nearby communities, notably Dowell and Olivet, also flourished.

Like other tidewater communities of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Solomons was isolated, close-knit and self-sufficient. Roads were few and became impassable in bad weather. By 1915, the state provided a road from Solomons to Prince Frederick, the county seat of government. Horse and ox-drawn wagons were the chief means of transport by land. Solomons’ link with the outside world was the twice-weekly steamboat from Baltimore. The arrival of the steamboat was a source of entertainment and great activity for the entire community. The steamboats provided supplies for the inhabitants of the area as well as provisions for the local stores. The steamer also provided a comfortable means to make occasional visits to Baltimore to shop and visit friends and relatives at the various stops along the route. Every family had its own boat that was used as people use the automobile today.

Like other tidewater communities of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Solomons was isolated, close-knit and self-sufficient. Roads were few and became impassable in bad weather. By 1915, the state provided a road from Solomons to Prince Frederick, the county seat of government. Horse and ox-drawn wagons were the chief means of transport by land. Solomons’ link with the outside world was the twice-weekly steamboat from Baltimore. The arrival of the steamboat was a source of entertainment and great activity for the entire community. The steamboats provided supplies for the inhabitants of the area as well as provisions for the local stores. The steamer also provided a comfortable means to make occasional visits to Baltimore to shop and visit friends and relatives at the various stops along the route. Every family had its own boat that was used as people use the automobile today.

Entertainment had to be provided by the residents of Solomons. In the summer, children and adults would sit under the cool shade of the trees that stood near the town well. Swimming among the children and sailing parties for the adults were quite popular pastimes. When the creeks and rivers froze, skating was the sport of the day.

Entertainment had to be provided by the residents of Solomons. In the summer, children and adults would sit under the cool shade of the trees that stood near the town well. Swimming among the children and sailing parties for the adults were quite popular pastimes. When the creeks and rivers froze, skating was the sport of the day.

Many local chapters of fraternal clubs were organized in this thriving community. Solomons took pride in a baseball team that played teams in other communities in the neighboring counties and as far away as Washington and Baltimore. Local talent also found an outlet in locally produced plays and theatricals. The most anticipated entertainment was the arrival of the James Adams Floating Theater. The theater carried a drama troupe and orchestra that performed matinees and evenings, usually for a week’s stand.

Making a living from the water required physical stamina and skill. Second jobs were often a necessity and at an early age, boys were expected to work after school to help the family with expenses.

With the arrival of the first automobile on Solomons around 1910, a way a life was irrevocably changed. Former resident Ethelbert Lovett recalled, “when word came down that the first automobile was on its way to Solomons, Miss Susie Magruder, the principal of our three-room school, dismissed us for this historic occasion. Workmen in the shipyard dropped their tools and gathered around the new vehicle.” With the automobile came improved roads and new bridges and two other marvels of the modern age – the telephone in 1899 and electricity in 1928. With the completion of the Gov. Thomas Johnson Bridge in 1977, linking Calvert and St. Mary’s counties, Solomons had lost its isolation.

With the arrival of the first automobile on Solomons around 1910, a way a life was irrevocably changed. Former resident Ethelbert Lovett recalled, “when word came down that the first automobile was on its way to Solomons, Miss Susie Magruder, the principal of our three-room school, dismissed us for this historic occasion. Workmen in the shipyard dropped their tools and gathered around the new vehicle.” With the automobile came improved roads and new bridges and two other marvels of the modern age – the telephone in 1899 and electricity in 1928. With the completion of the Gov. Thomas Johnson Bridge in 1977, linking Calvert and St. Mary’s counties, Solomons had lost its isolation.

During the first decade of the twentieth century, Solomons prospered. Many of the communities largest homes were built at this time. But, by the late 1920s, the region’s economy began to falter and declining oyster harvests and fish production forced watermen to look elsewhere for a living. Many local boatyards went out of business as the demand for workboats decreased. M. M. Davis and Son turned to building other types of crafts, such as custom yachts. Solomons began to show a steady growth in the business of providing recreation to “outsiders” – beginning with summer boarding houses and charter boat fishing in the early years of the century.

The Great Depression was devastating to the economy of Solomons, but even more devastating was the greatest natural disaster to hit Solomons – the August 23, 1933 storm. The lower half of the island was submerged, oyster beds and packing houses were destroyed and the steamboat wharf was torn away. Many boats were washed away, damaged, lost or destroyed.

During the 1930s the M.M. Davis & Son Shipyard produced many fine wooden yachts that brought international fame to Solomons. The High Tide, for example, owned by Eugene DuPont, won nearly every race she entered until she was so heavily handicapped that DuPont refused to race or sell the Davis-built yacht.

During the 1930s the M.M. Davis & Son Shipyard produced many fine wooden yachts that brought international fame to Solomons. The High Tide, for example, owned by Eugene DuPont, won nearly every race she entered until she was so heavily handicapped that DuPont refused to race or sell the Davis-built yacht.

Perhaps the best known Solomons-built yacht was the Manitou, built in 1937 for James R. Lowe. She won the Detroit to Mackinaw Straits race, and was sailed by former President John. F. Kennedy while she was owned by the U.S. Coast Guard. White Cloud, also built by M. M. Davis & Son, later won the same race. Today, little boatbuilding is done at Solomons. Charter-boat fishing, recreational boating, and tourism are the major activities.

New wealth was brought to Solomons when America entered World War II. When freedom and liberty faced their darkest hours in World War II, Solomons was chosen by the Allied command to be the staging area for amphibious invasion training. The lessons learned in Solomons proved invaluable on D-Day, Tarawa, Guadalcanal,, and numerous other successful (if costly) operations. Three navy bases were established at the mouth of the Patuxent River. These three facilities made a major contribution to the war effort and brought new jobs to local residents. Between 1942 and 1945, the population of Solomons increased from 263 to more than 2,600. And during this time, it was the local watermen who suffered the most as oystering and crabbing locations were disrupted by the military activity. For more information about the Naval Amphibious Training Base Solomons, go to www.CradleOfInvasion.org

Post war population growth and development, changing economic patterns, and improved communications and transportation brought an end to the isolated community that was Solomons. Restaurants and gift shops have replaced general stores and grocery stores of former years. State-of-the-art hotels and quaint Bed & Breakfast inns have replaced much of the old landscape. Solomons’ focus still lies with the waters nearby as marinas, marine suppliers, charter boat operators, the pilot station and other water-related businesses thrive in this sleepy waterside town. Tourism is now an important part of the economy of Solomons.

Post war population growth and development, changing economic patterns, and improved communications and transportation brought an end to the isolated community that was Solomons. Restaurants and gift shops have replaced general stores and grocery stores of former years. State-of-the-art hotels and quaint Bed & Breakfast inns have replaced much of the old landscape. Solomons’ focus still lies with the waters nearby as marinas, marine suppliers, charter boat operators, the pilot station and other water-related businesses thrive in this sleepy waterside town. Tourism is now an important part of the economy of Solomons.

Read the following to find out more about Solomons: How Things Have Changed: Solomons During the Twentieth Century, Part I – 1900-1949